The Hidden Forces Behind Flange Leaks — Why You Need Strongbacking

When repairing leaking flanges in process piping, engineers often specify strongbacks — structural restraints added to prevent flange separation during or after leak repair. To many technicians in the field, this can seem unnecessary, especially when the existing studs look sound and the joint was holding pressure fine before the repair.

So why add strongbacks after installing a clamp or sealant injection repair when they weren’t needed before? Let’s dive into the cause, effect, and consequences of this critical engineering consideration.

Understanding the Original Flange Design

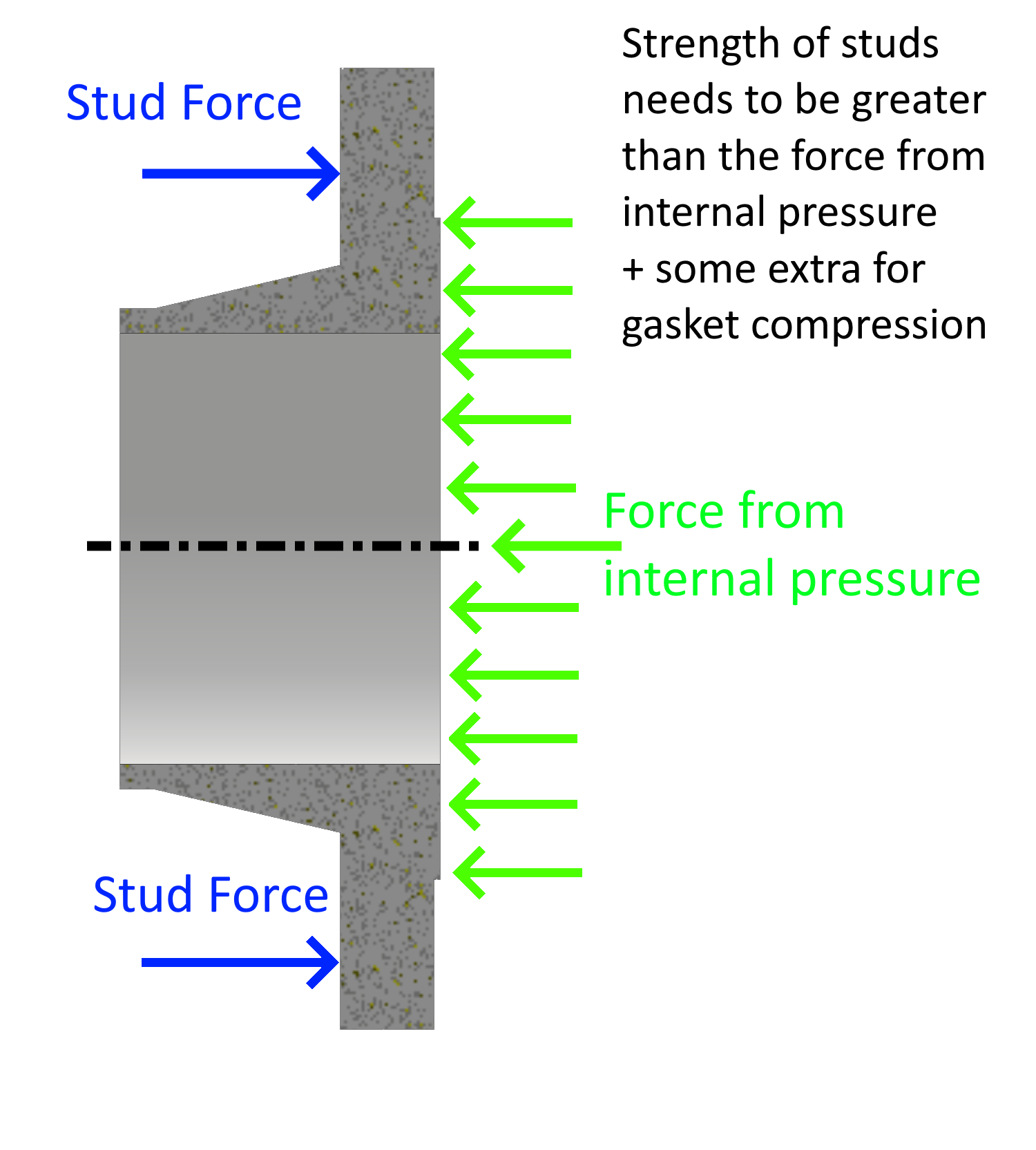

A flange joint’s primary job is to contain internal pressure and maintain a seal at the gasket interface. When a flange is designed, the studs (bolts) are carefully sized to:

Contain the internal pressure load acting on the gasket area.

Provide gasket compression by maintaining adequate bolt tension.

The internal pressure within the pipe acts outward, trying to separate the flanges. The effective pressure area extends only to the inner edge of the gasket. As long as the gasket is intact and sealing properly, all pressure-induced loads are resisted by the studs — and the joint remains stable.

What Changes During a Flange Clamp Leak Repair

When a leak occurs and a clamp or injection repair system is installed, we unintentionally change the geometry and load path of that flange system.

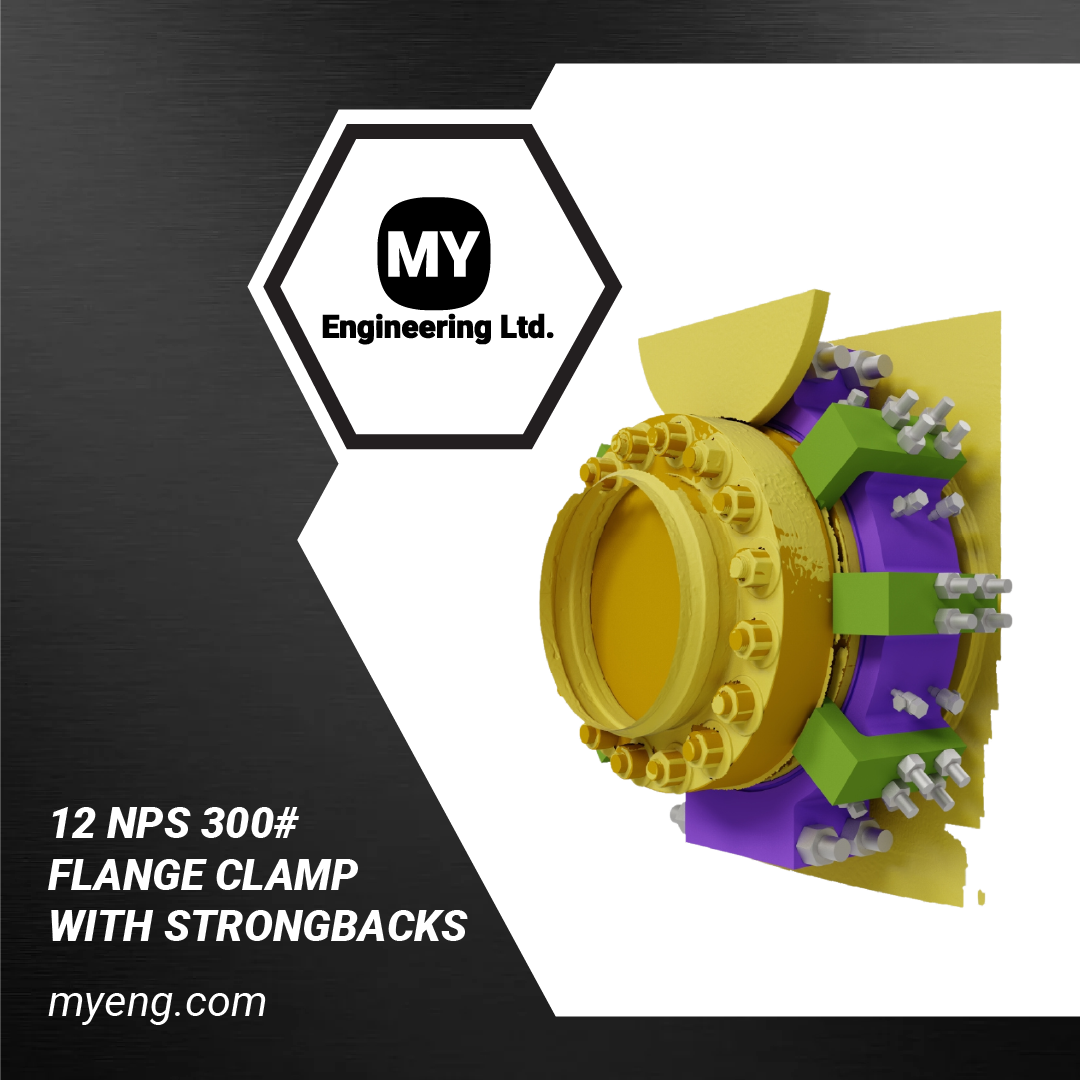

Most clamp-style repairs — such as flange clamp, tongue clamp, or wire and pen designs — seal by enclosing the flanges and injecting a sealant around the joint. The clamp typically seats around the outer diameter of the flanges, not just the gasket surface.

This introduces a critical shift in behavior:

The pressure boundary now extends beyond the gasket, sometimes all the way to the outside edge of the flange.

The effective pressure area increases, meaning the same internal pressure is now acting on a larger surface.

The studs that were originally sufficient for the smaller area may now be under-designed for the new, expanded load.

The Cause: Expanded Pressure Envelope

Once sealant is injected, it fills gaps and voids around the studs and between the flange faces. From an engineering perspective, we must assume the worst-case scenario: The internal pressure could act across the entire area up to the outer flange diameter.

While the sealant may theoretically stop the pressure at the gasket line, there is no reliable way to verify this. Therefore, the prudent design approach is to assume the pressure acts on the full face.

This shift dramatically increases the tensile load on the flange studs. In some cases, the original studs have enough reserve strength to handle the additional load, but in many, they do not — especially when corrosion, material fatigue, or high-pressure conditions exist.

The Effect: Risk of Flange Separation

Without additional restraint, the increased force can cause:

Flange separation — a widening gap between the flanges.

Stud overstress or elongation, leading to bolt failure.

Loss of seal integrity in the repair clamp or injected sealant.

Catastrophic release of process media, particularly hazardous in high-pressure or high-temperature systems.

Strongbacks act as external braces, distributing the load and preventing the flanges from spreading apart. They reintroduce the structural containment that the original flange design provided — but for the new pressure boundary.

Alternatives to Strongbacking

While strongbacking is the most common solution, it’s not always the most convenient. It can add significant bulk and cost to a repair package. In some cases, engineers may recommend hot bolting — the process of sequentially replacing the flange studs while the system remains pressurized. This allows upgrading to higher-strength studs that can safely handle the increased loads without needing external restraints.

However, hot bolting requires:

Detailed engineering analysis,

A safe, controlled environment,

Skilled personnel and appropriate safety measures.

When feasible, it can reduce the size and complexity of the repair, but it must always be justified by proper calculations and safety reviews.

The Implications of Skipping Strongbacks

Ignoring strongback requirements can have serious consequences:

Structural failure of the flange joint under pressure.

Progressive leaks as flange separation increases.

Repair failure, undoing the sealant or clamp work.

Potential safety hazards, equipment damage, and environmental release.

Strongbacking is not simply a “belt and suspenders” measure — it’s a structural safeguard that compensates for changes in pressure loading caused by the repair method itself.

Final Thoughts

Flange leaks are among the most common maintenance challenges in process industries, and temporary or permanent repair systems have become increasingly sophisticated. But engineering fundamentals don’t change — when the pressure boundary shifts, so do the forces acting on your fasteners and structure.

Strongbacking is, at its core, a way to restore the mechanical integrity of the joint after we’ve changed how it behaves.

Understanding this simple cause-and-effect relationship helps prevent dangerous assumptions — and ensures that repairs remain safe, reliable, and compliant.

If you found this information useful and want to learn more about advanced leak repair methods, don’t forget to subscribe to our channel or join our mailing list. We share new insights and tutorials regularly—stay ahead of your maintenance challenges by staying informed.